EONOMICS of HAPPINESS 2014 - An unspoken story of India (Part-2)

|

| Yoji Kamata from Japan with his model of Localisation |

Globalisation and Environment

In 1992, soon after heralding in the new economic

policies constituting globalization, the then Finance Minister of India (now its Prime Minister) Manmohan Singh

delivered a lecture on environmental aspects of the reforms in Delhi. His main argument was that

environmental protection requires resources, which would be created by the new

policies. Two decades later, has his prescription worked?

Broadly, economic globalisation since 1991

has had the following impacts:

Rapid

growth of the economy has required a major expansion of infrastructure and

resource extraction, and encouragement to wasteful consumption by the rich. The

economy has tended to be demand-led, with no thought given to how much demand

(and for what purpose) is to be considered legitimate and desirable, and what

its impacts are.

Liberalization

of trade (exports and imports) has had two consequences: rapid increase in

exploitation of natural resources to earn foreign exchange, and a massive inflow

of consumer goods and waste into India (adding to a rapidly rising

domestic production). This has created serious disposal and health problems,

and affected traditional livelihoods in forestry, fisheries, pastoralism,

agriculture, health, and handicrafts.

Environmental

standards and regulations have been relaxed, or allowed to be ignored, in the

bid to make the investment climate friendlier to both domestic and foreign

corporations.

The

opening up of the economy to foreign investment is bringing in companies with

notorious track records on environment (and/or social issues), with demands to

further relax environmental and social equity measures. Domestic corporations

have also grown considerably in size and power, and now make the same demands.

Privatisation of various

sectors, while bringing in certain efficiencies, is encouraging the violation

or dilution of environmental standards.

Had Manmohan Singh’s assertion worked, by now we should have

seen a spate of measures and programmes to protect India’s environment. But the

ecological crisis has only intensified. This, we show below, is an inherent and

inevitable outcome of the globalization process. Just as the trickle-down

theory does not work for the poor, so too the ‘having the resources to invest’

assertion does not work for the environment.

We should clarify here that criticism of a number of sectors and

activities below, does not mean we are per se against them. We are not saying

there should be no mining, no floriculture, no fishing, no exports and imports,

and so on. What is crucial is to ask not only whether we need these, but to

what extent, for what purpose, and under what conditions, questions that are

currently shoved under the carpet. Second, many of the trends described below,

are not necessarily a product of current globalization. Many of them have roots

in the model of ‘development’ we have adopted in the last five-odd decades,

and/or in underlying problems of governance, socio-economic inequities, and

others. However, the phase of globalization has not only greatly intensified

these trends, it has also brought in new elements that considerably enhance the

dangers of this model to India’s

environment and people.

Infrastructure

and materials: Demand is the god

With a

single-minded pursuit of a double-digit economic growth rate, demand achieves

the status of a god that cannot be questioned. The need for infrastructure or

raw materials or commercial energy is determined not by the imperatives of

human welfare and equity, but by economic growth rate targets, even where,

growth rates may have no necessary co-relation with human welfare.

The last couple of

decades have therefore seen a massive increase in new infrastructure creation

(highways, ports and airports, urban infrastructure, and power stations). This

has meant increasing diversion of land, mostly natural ecosystems like forests

and coasts, or farms and pastures.

Between 1993-94 and

2008-09 mineral production in India

has risen by 75%. This is manifested in a rapid rise in forest land diverted

for mining. If the nearly 15 lakh ha. of forest land diverted for mining since

1981 (when it became mandatory for non-forest use of forest land to be cleared

by the central government): 1981-92: 13,000 ha. (8.7%) 1992-2002: 57,000 ha.

(38.2%)2002-2011: 79,000 ha. (53%)

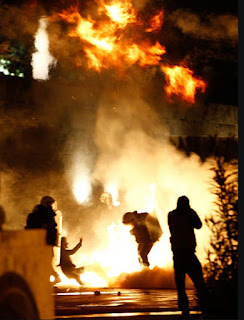

The ecological and

social impacts have been horrifying. The blasted limestone and marble hills of

the Aravalli and Shivalik Ranges, the cratered iron ore or bauxite plateaux of

Goa, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha, the charred coal landscapes of eastern India,

and the radioactive uranium belt of Jharkhand, are all witness to the worst

that economic ‘development’ can do.

Since 1991, some of the world’s

largest mining companies are investing in India. This includes Rio Tinto Zinc

(UK), BHP (Australia), Alcan

(Canada), Norsk Hydro (Norway) Meridian

(Canada), De Beers (South Africa,

Raytheon (USA), and Phelps Dodge (USA). Many of these have as bad or worse

environmental and socialrecords as India’s

own mining companies.

The lack of

regulation in the mining sector, an inevitable consequence of a demand-driven

economy that is trying to meet the greed of India and the world, is clearly

indicated in the spate of exposes regarding illegal. In Karnataka alone, 11,896

cases of illegal mining were detected between 2006 and 2009; in Andhra, 35,411

cases.

If the real aim of human society is happiness, freedom, and prosperity,

there are indeed many alternative ways to achieve this without endangering the

earth and ourselves, and without leaving behind half or more of humanity. This

applies to India

as to any other country, though the specifics of the alternatives will vary

greatly depending on ecological, cultural, economic, and political conditions.

Broadly, an alternative framework of human well-being could be called

Radical Ecological Democracy (RED): a social, political and economic

arrangement in which all citizens have the right and full opportunity to

participate in decision-making, based on the twin principles of ecological

sustainability and human equity. Ecological sustainability is the continuing

integrity of the ecosystems and ecological functions on which all life depends,

including the maintenance of biological diversity as the fulcrum of life. Human

equity, is a mix of equality of opportunity, full access to decision-making

forums for all (which would include the principles of decentralization and

participation), equity in the distribution and enjoyment of the benefits of

human endeavour (across class, caste, age, gender, race and other divisions),

and cultural security.

The above information is the work of Ashish Kothari .He has been Co-Chair of the IUCN Inter-commission Strategic Direction on Governance, Equity, and Livelihoods in Relation to Protected Areas (TILCEPA) (1999-2008), and in the same period a member of the Steering Committees of the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA), and IUCN Commission on Environmental, Economic, and Social Policy (CEESP). He has served on the Board of Directors of Greenpeace International, and currently chairs Greenpeace India’s Board. He has also been on the steering group of the CBD Alliance.

Comments

Post a Comment