ECONOMICS OF HAPPINESS 2014 - An Unspoken Indian Story (PART- 1)

India’s meteoric economic rise in

the last two decades has been impressive.

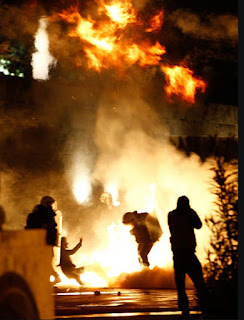

There is however a dark side to it, hidden or ignored.

Well over half its people have been left behind or negatively impacted; and there have been irreversible

blows to the natural environment Globalised development as it is today is

neither ecologically sustainable nor socially equitable, and is leading India

to further conflict and suffering There are, however, a range of alternative approaches

and practices, forerunners of a Radical Ecological

Democracy that can take us all to higher levels of well-being, while sustaining the

earth and creating greater equity

According to the

Tendulkar Committee on poverty estimation, which submitted its report to the Planning

Commission in 2009, the proportion of people who were poor in India in

2004-05 was 41.8% in rural areas and 25.7% in urban areas. The poverty lines

used to reach these numbers were Rs.15 per capita a day in villages and a bit

less than Rs.20 a day in towns and cities.

•

Over 80% of Indians live below its current per capita income

of Rs.150 a day.

• India

has the world’s largest number of undernourished people, more than all of

sub-Saharan Africa’s countries put together.

FAO’s estimate for the period 2004-06 is 251 million, a fourth of the country’s

population. This is only partly caused by increases in population and a rise in

life expectancy.

The number of

physically displaced and project-affected people, as a consequence of

‘development’ projects in India,

is estimated to be about 60 million since 1947. According to the Planning

Commission, in an assessment of about 21 million of these displaced persons,

over 40% are adivasis (tribal), even though adivasis constitute only 8% of

India’s total population.

•

There were 49,000 slums in Indian cities, according to NSS

surveys done during 2008-09. A 2003 UN study shows that over half of India’s urban

population lives in slums (including resettlement colonies). Across the world

one in three people live in a slum.

•

Employment in the formal (organized) sector of the Indian

economy has remained virtually stagnant around 27 million workers between 1991

and 2007. They constitute less than 6% of India’s overall labour force.

•

The daily per capita availability of cereals and pulses fell

from 510 grams in 1991 to 443 grams in 2007.

•

In April 2009, there were 403 million mobile users in India.

About 46% of them, or 187 million, did not have bank accounts. Only 5.2% of India’s 600,000

villages even have bank branches, leaving most farmers in the clutches of

moneylenders.

•

200,000 farmers committed suicide in India during 1997-2008, as a

consequence of being trapped in debt (which has risen dramatically since

reforms began). On average an Indian farmer has killed himself (much more

rarely, herself) every 30 minutes during these ten years.

• According to the

2009 Nielsen survey, 2.5 million of 220 million households in India owned both a car and a

computer. Only 0.1 million of the households could also afford a holiday

abroad.

Almost 60% of Indians

do not yet have proper sanitation facilities. According to UNICEF, improved

drinking water sources are available to 88% of the population (compared to 72%

in 1990).

A

high-net-worth-individual (HNWI) is a millionaire, someone with net investible

assets (other than owned homes, land and/or property) of at least $ 1 million

(Rs.4.5 crores). According to Merrill Lynch, in India there were 126,700 such

people in 2010. Though they make up only about 0.01% of the country’s

population they are worth about a third of its GDP.

According to a survey

by National Election Watch (NEW) the number of dollar millionaires (worth over

Rs.4.5 crores) in the present Lok Sabha has almost doubled to 300 (out of 543

members) since the last General Election in 2004. The 543 MPs are worth close

to Rs. 2800 crores ($560 million), making the average MP a dollar millionaire.

The 64 union cabinet ministers account for $100 million.

Privatization is increasingly being extended to natural

resources also. Long sections of rivers, such as the Sheonath, Kelu and Kukrut

rivers in Chhattisgarh, have been commodified and sold to corporate buyers in

different parts of India.

State of the

environment

According to a recent report, India has the world’s 3rd largest ecological

footprint, after the USA and

China.

Indians are using almost twice the sustainable level of natural resources that

the country can provide. The capacity of nature to sustain humans has declined

sharply, by almost half, in the last four decades or so.

The per capita

ecological footprint of the wealthiest Indians (top 0.01%) is 330 times that of

the poorest 40% of India’s

population. It is over 12 times that of the footprint of the average citizen in

an industrialized, high-income country. The footprint of the richest 1%

(inclusive of the wealthiest) of Indians is two-thirds that of the average

citizen of a rich country and over 17 times that of the poorest 40% of people

in India.

Thus, a person who owns a car and a laptop in India consumes roughly the same

resources as 17 poor Indians. Such a person consumes roughly the same resources

as 2.3 average “world citizens” (the world per capita income being about

$10,000 per annum in 2007).

According to the

MoEF State of Environment Report 2009 the “food security of India m ay

be at risk in the future due to the threat of climate change leading to an

increase in the frequency and intensity of droughts and floods, thereby

affecting production of small and marginal farms.” A significant decrease in

crop yields is expected across the country.

While

India’s

present share of global carbon emissions is about 8%, as a rapidly growing

economy it is rising every year. India’s per capita emissions are expected to triple by 2030 if present

trends continue.

Exports: Selling our future

Spurred on by active

governmental encouragement, India’s

exports grew at an annual rate of over 25% from 2003-04 onwards, reaching

US$300 billion in 2011- 12. Assuming that some level of exports is desirable or necessary, a responsible policy would have at least the following key

principles:

Access of the

country’s citizens to the products being considered for export is not

jeopardized by reduced physical availability or increased cost

Extraction or

manufacture of these products is ecologically sustainable;

Rights of local

communities from whose areas the resources are being extracted are respected;

and These communities

are the primary beneficiaries.

Unfortunately, exports under globalization have violated each of these

principles. Like mining, marine fisheries have been a key target. Exports of

marine products have risen from 139,419 tonnes in 1990-91, to 602,835 tonnes in

2008-09. From a handful of products being sent to about a dozen countries, we

now export about 475 items to 90 countries. India is now the 2nd largest

aquaculture producer (in quantity and value) in the world.

Sounds good, but at what cost?

One study showed

that in the states of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, the social and

environmental costs of shrimp aquaculture were 3.5 times the earnings (annual

losses: Rs. 67280 million; annual earnings: Rs. 17780 million). As areas get

converted to shrimp farming, local fish that are the staple food of local

communities, like mullets (Mugilidae) and pearl spot (Etroplus

suratensis), are eliminated. As marine capture fisheries have also grown to

about 3 million tonnes in 2008, there is evidence of over-fishing in the

territorial waters (though not in the deeper seas), and overharvesting of

several species. This, according to the Report of the Working Group on

Fisheries for the 10th 5-Year Plan, is mainly due to the use of the seas as

‘open access’ with no tenurial rights given to traditional fishing communities.

Technologies have also changed.

The government claims that big operators under the new policies will be allowed to fish only

in deep waters, where traditional fisherfolk do not go. But past experience has

shown that trawler owners find it convenient and cheaper to fish closer to

shore. Also, trawlers continue to be illegally used in the fish-breeding

season. Physical clashes between trawler owners and local fisherfolk remain

common.

Internal liberalization: Towards a

free-for-all?

All industrial

countries of the world have gone through a process of tightening environmental

standards and controls over industrial and development projects, for the simple reason that project authorities and corporate houses on their own have not shown environmental and social responsibility. In India, there is a reverse process going on.

standards and controls over industrial and development projects, for the simple reason that project authorities and corporate houses on their own have not shown environmental and social responsibility. In India, there is a reverse process going on.

In 1994 a

notification was brought in, under the Environment Protection Act 1986, making

it compulsory for environmental impact assessments (EIAs) to be conducted for

specified projects. While this notification was weak, and subject to various

kinds of implementational failures, it nevertheless injected some degree of

environmental sensitivity in development planning. However, it continued to be

seen as a nuisance by industrialists, politicians, and many development

economists. A committee set up by the Indian government pointed to the need to

reduce the environmental hurdle, and a World Bank-funded process to assess

environmental governance, also suggested reforms (read: weakening) of this and

other regulatory measures. Thus in 2006, despite considerable civil society

opposition, the government changed the notification, making it much easier for

industries and development projects to obtain permission, and weakening the

provisions for compulsory public hearings. The notification also took tourism

off the list of projects needing environmental clearance, despite evidence that

in many places this was a sector out of control

http://sangeethasriram.blogspot.in/2014/03/quotes-on-globalisation.html has some write up on the various quotes of the people in the leadership

http://sangeethasriram.blogspot.in/2014/03/quotes-on-globalisation.html has some write up on the various quotes of the people in the leadership

The above is an extract of the information compiled by Ashish Kottari - an Environmentalist

|

| Samdhong Rinpoche the former PM of Tibet Govt in exile speaks |

|

| Kishor Jagirdar with Samdhong Rinpoche - The spiritual Leader and Former Prime Minister of the Tibet Govt in Exile |

|

| Manish Jain, Helena Norberg-Hodge, Samdhong Rinpoche |

Comments

Post a Comment